Laser Images Bring the Old King’s Highway to Life

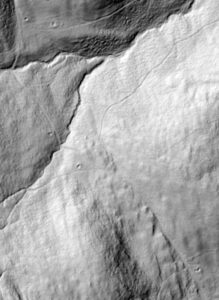

The Old King’s Highway has disappeared under a veil of trees but the impression left in the ground can be seen starting at the bottom of the photo where a line veers left from Old Town Farm Road. The cellar hole of the home of Joel and Lydia Simonds can be seen in the left center of the photo. Secondary roads and stonewalls are also visible. This image was created with LiDAR, a technology that uses lasers to generate topographic maps. LiDAR shoots and collects up to a half-million data points per second, creating a 3D map of the landscape that is accurate to within 10 centimeters. When a LiDAR-equipped aircraft flies over a wooded area, laser beams penetrate the canopy and bounce back. An algorithm then factors out the vegetation, creating a topo map. This stagecoach route from Boston to Montreal was laid out in 1763 and flourished until railroads were established in White River Junction in 1848. The Old King’s Highway disappeared from maps by 1910.

Back in the day when one went from Boston to Montreal by stagecoach, the coach would cross the Connecticut River from West Lebanon, pass the Hartford meetinghouse in the center of town, rumble through Quechee Village, and continue north up Seaver Hill along what was called the Old King’s Highway to Pomfret. The last house in Hartford on this old road was built by John Braley in 1796. He and his wife Mary owned land on both sides of the highway and raised thirteen children there.

In 1814, the Braley’s daughter Lydia married Joel Simonds and they lived in Northfield, VT when their first child, Daniel, arrived in January 1815. Joel and Lydia had moved to Hartford by the time daughter Mary was born in December. When John Braley died in 1819, they purchased his home on the Old King’s Highway.

Joel and Lydia had fourteen children in their small home. The Simonds children would likely have attended the one-room Birch School down the hill on Quechee West Hartford Road. Joel was assisted in the fields by his sons Daniel, Charles, Rufus, and Horace who all became successful farmers.

In 1832, the Simonds family was among many across America to be struck by illness. Ten-month-old John Simonds died on April 28, and his brothers Albert and Seth died on May 5. The cause of these deaths is not known. Consumption was the leading killer at the time but a severe cholera epidemic swept the country in 1832. Joel and Lydia buried their boys next to their home. Over the years, illness also claimed Polly, John B., Horace, and Harriet Simonds. In 1851, Joel also buried his infant grandson, Charles Simonds. In time, Joel enclosed the little cemetery with granite posts and wrought iron rails. In 1853, he deeded the property to the town of Hartford hoping it would be permanently maintained.Despite these losses and the strain of subsistence farming, Joel and Lydia persevered with the support of family, friends, and faith. Their son Charles and his family lived next door and Daniel and Rufus were nearby. In 1863, Joel Simonds was listed among members of the Christian Society of Quechee Village.

There were three unions between the families of Joel Simonds and John Judd of Strafford, VT. Daniel Simonds married Sarah Judd in 1845. Lydia Simonds married Lyman Judd in 1851, and Rufus Simonds married Wealthy Judd a few years later.

In 1864, after fifty years of marriage, Joel and Lydia Simonds sold their property in Hartford and moved to Strafford where they spent their last years living with their daughter Lydia Judd and her husband. Lydia Simonds died in 1873 and Joel survived her by three years. They are buried in Evergreen Cemetery in South Strafford.

Today, the hillside is covered with trees and there is no sign of the Old King’s Highway. All that remains of the Simonds home is a cellar hole, stonewalls, and scattered pieces of headstones.

But though the area is covered by a green canopy, the State of Vermont has done laser images, known as LiDAR, that show the path of the old highway, the outline of Joel’s fields, and a neat earthen rectangle around the house and cemetery. Straight lines suggest stonewalls on both sides of the old highway where crops were raised and animals grazed. A faint rectangle near the cellar hole may have been a barn.

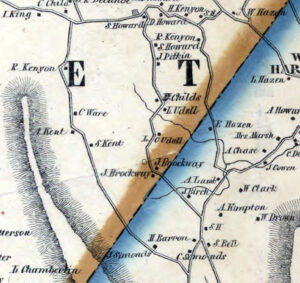

These LiDAR images also show old cellar holes further north on the Old King’s Highway in what is now Pomfret. A map from 1856 identifies owners as S. Kent, A. Kent, C. Ware, and R. Kenyon.

S. Kent left the cellar hole of a prosperous farmer and, across the highway, lies the foundation of a spacious barn. The fields of S. Kent lie to the east of the Old King’s Highway and the laser images suggest they were bounded by stonewalls. A secondary road connects the farm with Joe Ranger Road. A short way north along the highway was the cellar hole of A. Kent. Likely a son of S. Kent, his story needs further research.

Then one soon comes to the modest cellar hole of C. Ware with its central fireplace. It may have been the home of Camilla Ware who was born in Peacham, VT and moved to Pomfret with her parents Jonathan and Betsey Ware in 1813. In 1856 when the map showing the Old King’s Highway was printed, Camilla was the only member of the Ware family still living in Pomfret.

Jonathan Ware was a linguist, writer, teacher, lawyer, abolitionist, and historian. After graduating from Harvard in 1790, he studied law in Bennington, VT and moved to Peacham, VT to begin his career. At that time, he also helped start a newspaper called the Green Mountain Patriot.

One early source says that Jonathan, “was unfortunate in his practice and in money affairs,” so he closed his law practice and moved his family to Danville, VT. Jonathan and Betsey lost an infant daughter there in 1807. During the War of 1812, Jonathan served in the army for a time in Burlington and Plattsburgh. His son Jonathan Jr. also served and may have died during the war at age seventeen. He was buried in Pomfret in 1813 by which time the family had presumably moved to a rough little farm on the Old King’s Highway.

In addition to farming, Jonathan Ware continued to write. In 1814, he published a book about English grammar. He also completed an unpublished history of Vermont. To support his family, he traveled to Boston and New York to teach Greek for several years. Returning home, he tried to open a small school but it did not succeed.

Jonathan spent a dozen of his later years translating the Old Testament from Hebrew into Arabic, Greek, Latin, English, French, Spanish, Italian, German, Danish, and Russian, all on the same page. He was nearly finished but traveled to Boston to consult references and caught a lung infection that killed him in 1838. The book was bound and preserved at Harvard.

Jonathan Ware was civic minded and corresponded on issues such as slavery and government policies toward Native Americans with public figures like William Lloyd Garrison and Alden Partridge, founder of the military school that became Norwich University. Garrison published a tribute to Ware in his paper, The Liberator, after his death.

Jonathan’s wife Betsey was the oldest daughter of John Winchester Dana who was a successful farmer and one of Pomfret’s founders. Betsey Ware was likely the practical member of this scholarly household and it is possible her father assisted the family although he died the year they returned to Pomfret.

Camilla Ware was an apt student who learned at least six foreign languages but, like her father, never enjoyed success as a teacher. She assisted her father with his writing and, in 1858, published an abolitionist tract called Slavery in Vermont. Camilla died in 1871 and is buried with her family in Pomfret’s Hewittville Cemetery. This ended a remarkable and little known chapter in Pomfret’s history.

To the north along the highway, just below the Appalachian Trail, is the cellar hole of R. Kenyon. This may have been Remington Kenyon who came to Pomfret with his wife Jerusha around 1820. Jerusha Kenyon is buried nearby in the Bunker Hill Burying Ground. Remington Kenyon died in 1869 and his stone could be among several illegible markers near his wife.

Remington and Jerusha had four sons, Horace, Carlton, Albert, and Charles. A second cellar hole suggests that one of the sons may have built a home nearby, perhaps after the map was created in 1856. This may have been Horace Kenyon whose wife Philna and her twenty year-old son Edgar also rest in the Bunker Hill Burying Ground.

These residents of the Old King’s Highway likely knew each other, helped each other, and shared the hardships of that difficult time. When railroads replaced stagecoaches in the mid-1800s, a former lifeline of commerce was quickly engulfed by forest, properties lost value, and local residents moved on—leaving faint memories, distant descendants, and mysterious traces on LiDAR images.

Hartford Historical Society

1461 Maple St.

Hartford, VT 05047

(802) 296-3132

info@hartfordhistory.org