Winsor and Bertha Brown Breathe New Life

Into the Old Coolidge Farm

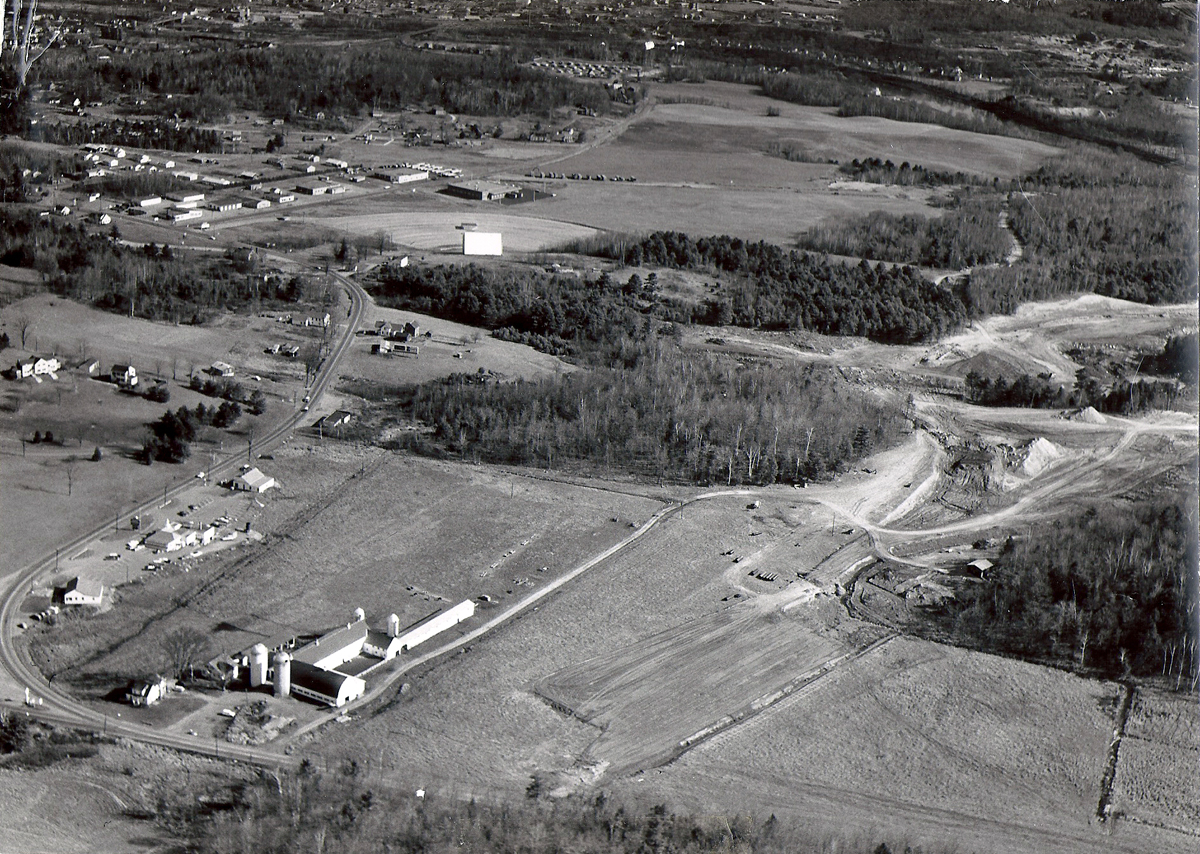

Ballardvale Farm, foreground, in the ’Sixties. Winsor and Bertha Brown raised five children in an old former schoolhouse near the road. Around the curve is the Howard Johnson’s restaurant that Winsor and partners opened in 1948. Winsor provided the land in exchange for stock in the company. In the ’Fifties, the Brown family raised hay on much of the land in this photo, including the site of the drive-in theater.

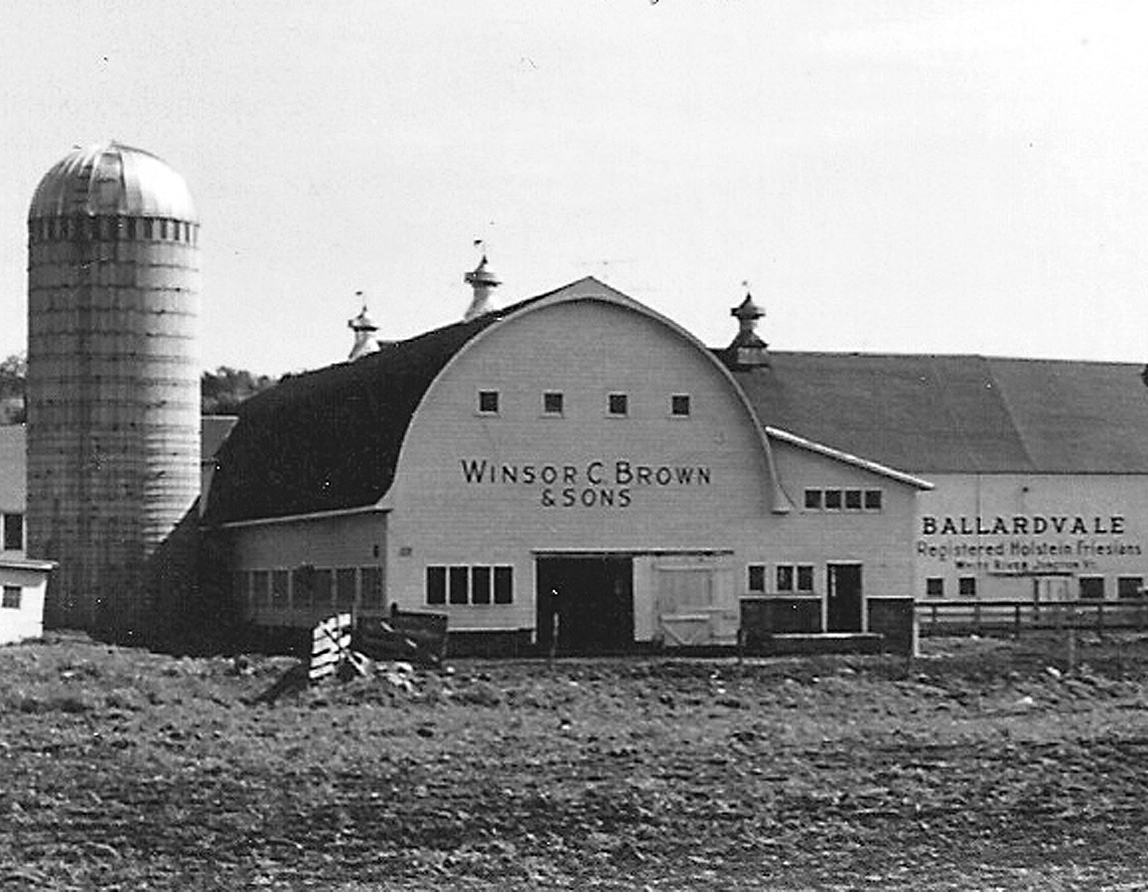

The Rutland Daily Herald published a brief note on June 2, 1934 that Winsor C. Brown had purchased the N.P. Wheeler farm on what is now Route 5 south of White River Junction. Wheeler was the former owner of the Hotel Coolidge and the words Coolidge Farm covered one side of the barn. The farm had been vacant since his death in 1930. “It was very run down,” says Winsor Brown’s oldest son David. Winsor bought it for back taxes and named it after his wife’s hometown of Ballardvale, MA.

Winsor Brown had married schoolteacher Bertha Hall in 1933. Winsor and Bertha came from farming backgrounds and, with modest loans from both families, they bought the old Wheeler place. Ballardvale Farm was a mix of old buildings and when Winsor visited a local bank for a loan to fix things up, one of the local bankers reportedly said, “Nice young man. Too bad he bought a farm that nobody’s ever succeeded at.”

But Winsor Brown had graduated from the Stockbridge School of Agriculture at the University of Massachusetts and interned with one of his professors, J.D. Abbott of Rockingham, VT. After that, he managed a large farm in Massachusetts for two years where he applied what he had learned at Stockbridge and resolved never to raise turkeys on his own farm. Winsor understood the science and business of farming, and he loved all of it.

Ballardvale Farm had a dairy barn with hayloft and a hog barn. The main residence was an old school house next to the road that had been moved onto the property years ago from over on the Old King’s Highway. It was a very early building framed with peeled poles. Another old building on the farm housed hired help.

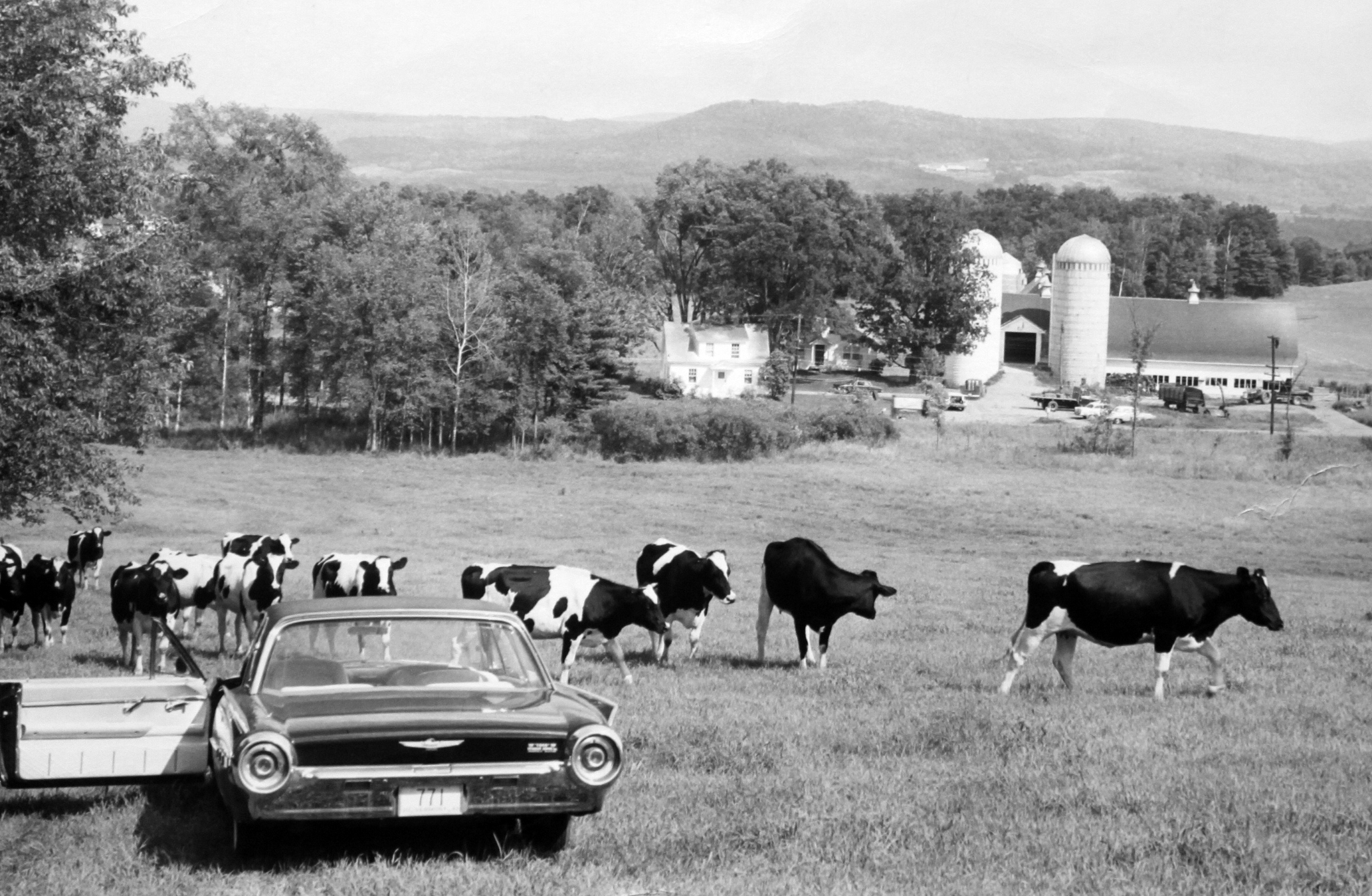

When they moved into the old school, Winsor and Bertha had no children and no livestock. But soon the farm was home to three boys, two girls, a flock of chickens, and some forty Holsteins. Winsor had learned to prefer Holsteins at Stockbridge. There was also a garden and Winsor was soon selling cauliflower and Blue Hubbard Squash to local stores. Every fall, he took at least one truckload of vegetables to the farmer’s market at Faneuil Hall in Boston.

Holsteins graze near a visitor’s T-bird.

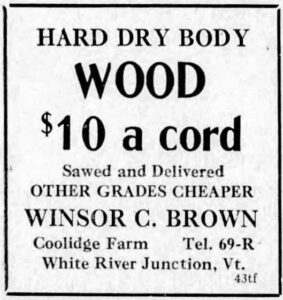

Firewood was another early cash crop. Winsor sold it for ten dollars a cord, delivered. “He was always looking to earn a little more money,” David recalls. “Dairy farmers only got a milk check once a month, and sometimes it wasn’t enough.”

David remembers being told about a huge setback his parents faced around 1936, the year he was born. “We had about thirty milkers out in a pasture that was near a cornfield, and the corn frosted. Well, the cows got out and ate the frosted leaves and got prussic acid poisoning. When my father went out to the barn to milk, many of them weren’t even standing and the rest had to be sold for beef. It was a disaster.”

Fortunately, Winsor knew a cattle dealer named Walter Clark in Union Village. “They went to Canada,” says David, “where they bought some Holsteins to supplement the herd and get a milk check. My father paid him back over time.”

Gordon Brown packs eggs in 1941. Each case had thirty-six dozen carefully wrapped eggs.

Winsor took an analytical approach to everything. He had always been a good student and David Brown credits his grandmother, Edna Cargill Brown, for helping Winsor become proficient at math and graduate from high school a year early. Edna had majored in math at Cornell College.

“My grandmother definitely taught him how to solve problems,” says David. “When we needed to know the capacity of a silo, we would pace out from the side to create a right triangle, then we’d figure that it’s forty feet high and twenty feet in diameter, so we could figure the square feet in the circle and finally the cubic feet. Then we would know how much silage it would hold. Next, we’d calculate how much silage we were going to get out of a field and whether it would fill the silo. He always had us thinking.”

Another calculation was needed to find the proper setting for the fertilizer spreader. “You only wanted to put so many pounds to the acre,” David recalls, “and we were handling 80-pound fertilizer bags. So he‘d have us put maybe five pounds in the spreader and then push it across a canvas on the driveway so we could set the thing to put out the proper amount. We were always thinking about these things.”

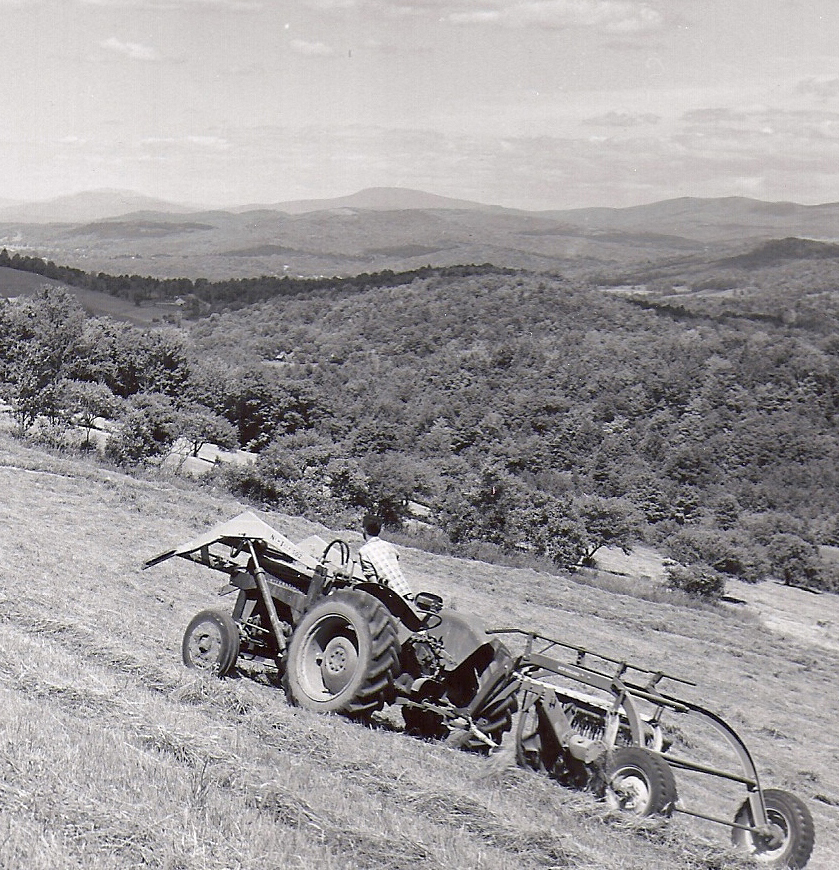

David Brown haying.

In 1939, The Landmark reported that Winsor Brown had built a “Connecticut-style” brooding house in which he was raising six hundred chicks. The twenty-four square-foot building was insulated with sawdust and heated by two wood burning brooder stoves. “We’d keep chickens for a year,” David says, “then we’d sell them and get another batch.”

When World War II started, Winsor Brown expanded production to twelve hundred chicks. This called for more buildings and a fenced-in chicken range across the road. Winsor crossed Barred Rock roosters with Rhode Island Red hens to produce broilers without pinfeathers. “In springtime when the grass turned green, the baby chicks would be feathered out,” David remembers, “so we put them over on the range. We made little A-frame houses for them out of wood and chicken wire.”

World War II increased demand for broiler chickens, so Winsor bought roosters and started shipping fertilized eggs by train to Wilmington, DE, where they were hatched and raised. “I used to hate working with roosters because they’d jump up and spur you in the knees,” recalls David. Every week, Winsor drove fifteen or twenty cases of eggs to the White River depot. Each case had thirty-six dozen carefully wrapped eggs.

Egg packing was one of many chores the Brown children helped with. David remembers many monotonous hours filling egg crates and listening to the Lucky Strike Hit Parade on the radio. Eggs were stored in the basement of the house where they were warmed by a coal-fired heater.

Ballardvale Farm in 1958. Winsor Brown stopped raising chickens in 1950 and doubled his dairy herd.

“My mother did all kinds of things with cracked eggs,” David says. “We had omelets and so on because they would be thrown away otherwise.” Bertha Brown cooked for her family and hired helpers on a kerosene stove with two burners on top and two more to heat the oven. She baked constantly and there was always something cooking on the stove.

Bertha also did laundry for everyone on the farm and, “farm laundry is dirty laundry,” says David. He recalls that his mother was meticulously organized and each day brought different activities between meals. “You never saw her sitting down,” says David.

Early in the war, Winsor Brown heard about a company in Enfield, NH, that needed pine boards to make ammunition boxes for the army so he looked around to buy a sawmill. “Well,” David says, “in 1928, there was a flood in Tunbridge that washed a sawmill into the White River. When I was about in first grade, my father and my uncle heard about it and pulled it out of the river. Then they brought it back to the farm, cleaned it up, and hooked it up to an old Gar Wood chain drive dump truck. The truck’s driveshaft connected with the saw through a universal joint and they ran it by pulling a rope tied to the truck’s throttle.”

David recalls that the truck’s steering wheel was disconnected so he and his brothers could sit in the cab and pretend to drive while their father cut lumber for ammo boxes, chicken houses, and other farm projects. Winsor also restored a shingle mill that he salvaged from the river, so the chicken houses had wooden shingles.

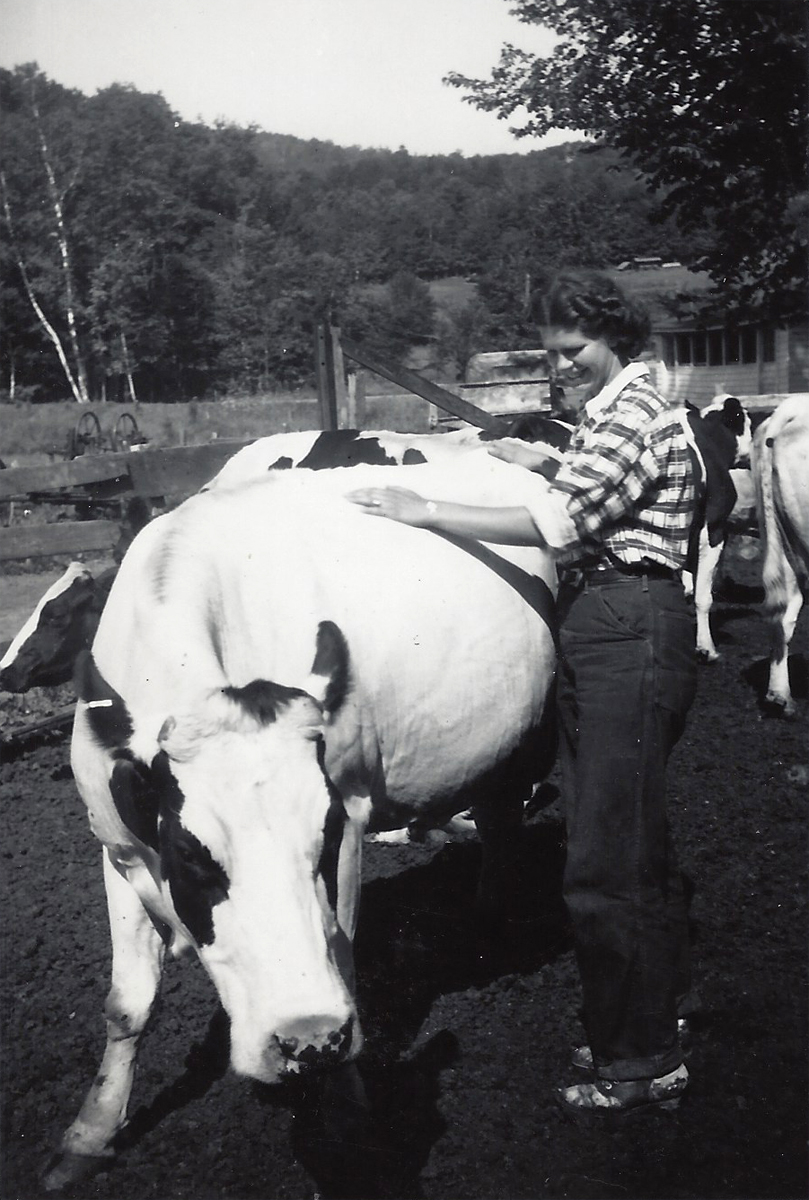

Patricia Ames was a student from Stockbridge School of Agriculture who interned at Ballardvale Farm and worked there during World War II. This photo from 1950 shows her with a Holstein named Mollie.

As able-bodied men were being drafted into the service, Winsor went to the draft board in Woodstock to see how many men could be deferred to help him maintain the farm. He was told that he and four additional men would qualify for deferments, but Winsor decided he just needed two helpers. “He did it by getting ahead of his time in mechanization,” says David.

“I’ll give you an illustration,” he continues. “A typical Vermont farm at that time used a two-bottom plow pulled by a small tractor. My father went to the bank and said, ‘I need a crawler tractor that will pull a three-bottom plow and I need to be able to pull a 14-foot disc harrow.’ They looked at him like he was crazy and told him that a crawler tractor was intended for construction rather than farming.

“He said, ‘No, that’s what I need. The land has a lot of heavy clay, it’s steep, and a wheel tractor won’t get the job done.’ So, he finally convinced them by figuring the acres per hour he could plow with a three-bottom plow and the increased crops he could produce in our short growing season. He showed that, with this kind of plow and tractor, he could get the crop in the ground in the last couple of weeks in May and have it knee high by the fourth of July.” After using his new crawler and plow for a year, Winsor was able to take a pro forma sheet to the bank showing that his projections had been correct.

“He said, ‘No, that’s what I need. The land has a lot of heavy clay, it’s steep, and a wheel tractor won’t get the job done.’ So, he finally convinced them by figuring the acres per hour he could plow with a three-bottom plow and the increased crops he could produce in our short growing season. He showed that, with this kind of plow and tractor, he could get the crop in the ground in the last couple of weeks in May and have it knee high by the fourth of July.” After using his new crawler and plow for a year, Winsor was able to take a pro forma sheet to the bank showing that his projections had been correct.

Winsor also adopted more efficient ways of harvesting hay, starting with one of the first balers in the area followed by a device that lifted bales onto a truck. When hay got to the barn, it was dropped onto a sling that lifted it to the hayloft and carried it through the mow along a track. Two men could operate the sling, which was much more efficient than using hayforks. “My father cut the whole labor factor down considerably,” says David.

Winsor Brown in the milking parlor with his daughter Marilyn.

During the war, farm tractors weren’t available so Winsor built what he called a “doodlebug” out of a 1938 Ford truck. He put a second transmission in it and shortened the wheelbase so it was the same length as a tractor. “He went to a construction site and got a pair of dump truck tires, chained them to the rims, and put them on the rear,” says David.

With two transmissions and those chains, it had more traction than a tractor and could pull a 200-bushel manure spreader. David remembers that, after the war, tractor dealers started to come around with new machines and his father would say, “Well, I’ll buy it if it’ll do what my doodlebug does.”

In 1944, Winsor Brown was mentioned in the Vermont Standard for having the most productive dairy cow in Windsor County. In 1946, Ballardvale Farm was one of the stops on a regional 4-H tour of successful poultry farms. That same year, Winsor Brown was one of nine Vermont Holstein breeders admitted to membership in the Holstein-Friesian Association of America.

In addition to running a busy farm in wartime, Winsor Brown served as chairman of the local OPA Price and Rationing Board. Based in an office in the Gates Block, he helped residents understand pricing policies and use rationing coupons. Some policies continued after the war. In 1946, Winsor placed a notice in The Landmark inviting local residents to a meeting where he would explain ongoing lumber price controls.

Winsor joined the board of the White River Rotary Club in 1945 and was elected president in 1947. In 1948, he served on a committee that helped organize a medical insurance program for local residents.

That same year, Winsor became a partner in the firm Cashman-Cairnie that issued stock to build a Howard Johnson’s restaurant in White River Junction. The restaurant opened on July 21, 1948 on land formerly owned by Winsor Brown across from the Veteran’s Administration Hospital on what is now Route 5. The Browns dined at the restaurant on special occasions and David recalls having many flavors of Howard Johnson’s ice cream in the family freezer. Winsor added a filling station next to the restaurant in 1952 at a cost of $8,420.

In 1950, Winsor Brown was elected to the Hartford School Board and became chairman of the Ways and Means Committee, which organized fund raising events. As chairman of the school board, he was instrumental in planning the Hartford Memorial School, one of Vermont’s first middle schools, and spoke at the dedication.

David recalls a milestone event for Ballardvale Farm that happened at breakfast one morning in 1950. “Breakfast was always when we decided what was going to happen that day or week,” he says. “We’d talk things over and then have a vote, which made us feel that we were participating in the decisions. Anyway, Dad said, ‘Which is it going to be–chickens or cows?’ Well, it was no discussion–cows.”

Turns out that was Winsor’s way of telling the family that things were going to change. Soon the chicken operation was gone and a new barn along Route 5 housed a milking parlor for another fifty head of cattle.

“The milking parlor had stalls where six cows could be lined up at the same time,” says David. “Milking required two people. When you walked along the stalls, the cows’ udders were right there chest high and you didn’t have to squat down like you do in a regular barn. The milking equipment came right down in each stall where you needed it.

“When one cow was finished, she left by the exit gate and went back to the barn by herself because there was silage there. Then you’d put a fresh bowl of grain in the stall for the next cow and she’d walk right in the entrance gate. We had a chalkboard to keep track of how much milk each cow gave. The more milk they gave, the more grain they got. The ones who were really milking got extra grain back in the barn.”

Doubling the herd allowed Winsor to afford a bulk milk cooler, which provided a competitive advantage and would eventually be required in all dairies. These expensive units forced many dairy farmers to either expand or go out of business. “My father said the only way we can pay for a bulk cooler was to produce more milk. It was a huge decision.”

More cows meant more manure. “We went from shoveling it into a wheelbarrow to using a conveyor system that pushed it from the stalls through gutters and out to the manure spreader,” says David. The changes allowed Ballardvale Farm to meet health requirements while becoming more efficient. No additional employees were needed.

But the larger herd required more food. Winsor built temporary silos out of snow fencing for a while. Then he bought a metal silo at a farm in Massachusetts, removed thousands of bolts, trucked it home, and reassembled it. He later built two more silos.

Winsor had previously leased a hundred acres on the former site of the White River Junction fairgrounds and now he added forty more acres to the south along Route 5. Gradually, he added several fields in Norwich for hay production and grazing. Ultimately, Ballardvale Farm encompassed over seven hundred and thirty acres including some woodland.

In 1954, Winsor received the “S” award from his alma mater, the Stockbridge School of Agriculture, for outstanding achievement in agriculture. He also became active in the Windsor County Farmer’s Exchange and was frequently mentioned in local papers for having the most productive dairy cow in the Central Pomfret Dairy Herd Improvement Association. In 1955, he received newspaper coverage every month for cows producing over 70 pounds of butterfat a day. In February 1956, one of his cows exceeded one hundred pounds a day.

That summer, Winsor invited local farmers to learn about fertilizing techniques at Ballardvale Farm and demonstrated a new hay crusher. Clearly, Winsor had made the old Coolidge Farm a success. Not only that, in 1957 he became a partner in a new Howard Johnson’s restaurant in Rutland that the newspaper noted was equipped with a $20,000 microwave oven.

In 1959, Winsor Brown was elected to the board of the Bellows Falls Cooperative Creamery. This was a challenging time for many small dairies trying to compete with larger farms using bulk tanks. He was re-elected to the board and named president in 1963. He led the organization through the difficult process of deciding that the creamery could only remain competitive by requiring all members to ship their milk in bulk tanks after March 31, 1964.

But in 1964, the creamery was plagued by rumors that its largest buyer was not going to renew their contract and that many members, including Winsor Brown, might be planning to leave the creamery or the dairy industry. In February, Winsor sent a letter to members confirming that there were very strong market pressures on the coop’s leading buyer but that no change had been announced. He also denied that he was planning to leave the dairy business.

In March, Winsor expanded on his plans in an interview with the Vermont Journal where he continued to encourage coop members that the industry was viable for those who worked efficiently, but he also announced changes at Ballardvale Farm. Construction of Interstate 91 would take eighty-six acres from the farm so he planned to reduce his herd to one hundred and sixty Holsteins that would be divided between the current farm and another one to be purchased by his son Gordon elsewhere in Vermont. That same issue of the Vermont Journal advertised an auction of seventy Holsteins at Ballardvale Farm.

In July 1964, Winsor announced the last shipment from Bellows Falls Cooperative Creamery to First National Stores, its largest customer for the previous forty-two years. The creamery work force would be substantially reduced but local customers would continue to be served and there were no plans to close the business.

But the end of the Bellows Falls creamery came late in 1965 when the board voted to be absorbed by the United Farmers of New England, which would transport milk directly from farms to stores. While many dairy farmers sold their herds, Winsor rebuilt his herd to a hundred and fifty head and his son Gordon established a new dairy farm in Brandon, Vermont.

In 1968, Winsor opened a seventy-two-unit motel in White River Junction next to his Howard Johnson’s restaurant. Bertha Brown served as secretary of the new corporation for ten years. Winsor also became a partner in a Howard Johnson’s restaurant in Brunswick, Maine.

Like her husband, Bertha Brown was active in the community. She died in January 1979 at age seventy-one. Winsor Brown died the following October, also at age seventy-one. He deeded a piece of Ballardvale Farm to each of his children and also gave the Town of Hartford one hundred acres on Hurricane Hill for use as a Town Forest. Winsor and Bertha now rest in a private cemetery on the hill above their farm.

Hartford Historical Society

1461 Maple St.

Hartford, VT 05047

(802) 296-3132

info@hartfordhistory.org